A Brief Parisian Autobiography in Three Parts (Part III)

wherein literary dreams are realized and reality sets in

(read Part I here and Part II here)

One does not discover new lands without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time.

Andre Gide

Life rarely changes in the moments you expect. With a mission to raise ten thousand dollars in three months, and no idea of how to use social media correctly (I didn’t have an Instagram and or Twitter account at the time), I turned to the only chance I had at securing pre-orders for Slim and The Beast: my real-life community.

I reconnected with old college friends via Facebook and told them about my novel about basketball, male intimacy, and growing up in North Carolina. By pre-ordering it for $25, they’d not only guarantee the book’s place on a bookshelf, but would also be participating in my literary career. I sent hundreds of individual emails to former teachers, family, friends, elders and acquaintances; I learned just how many childhood friends and their parents, many of whom I hadn’t spoken to in a decade, were interested in reading a story about our youth. One friend in Paris bought a dozen copies to send to his family in Ireland. Another invested hundreds of dollars in a single copy. But I connected with strangers, too: a student at a bus stop in London who contributed $100 to the novel, and a hospital nurse in Prague who’d read an excerpt online and had pre-ordered the novel to practice his English while working the night shift. Three months and 232 backers later, Slim and The Beast became the first published novel at Inkshares.

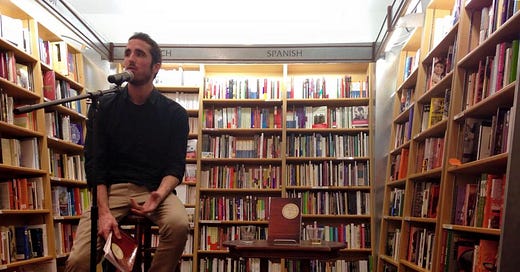

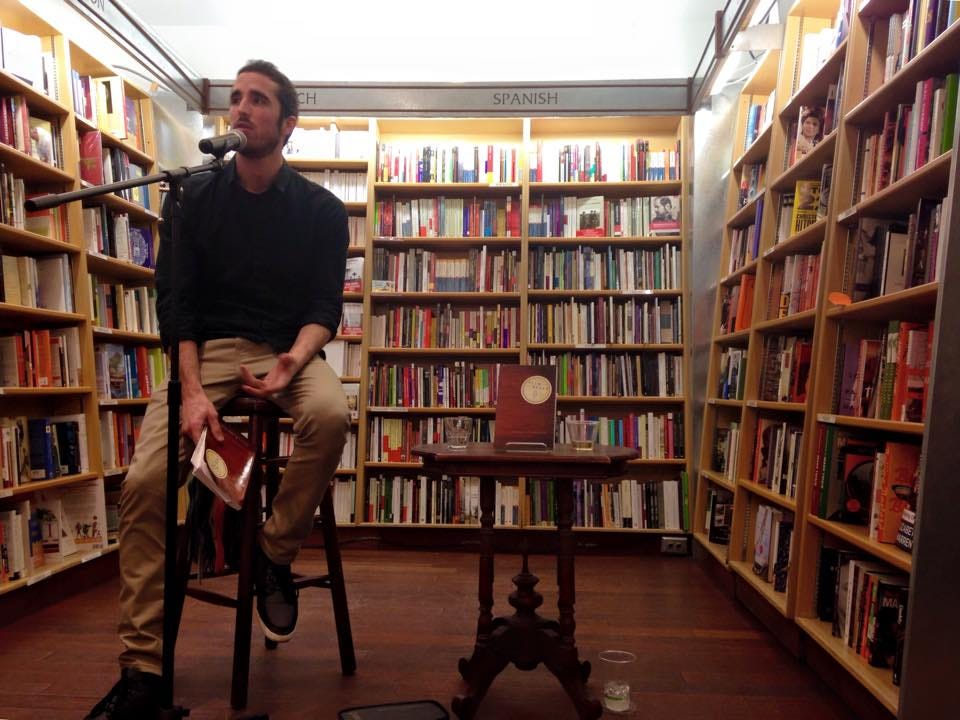

At twenty-seven years old, I was wilfully optimistic (and naïve) about the publishing industry. Still, I felt accomplished. Surely, I thought, a published novel meant I was on the way to making it, as the next months were paved with literary promise. I read and spoke at McNally Jackson’s in downtown Manhattan and at Shakespeare and Company in Paris. The reading in my hometown bookstore (Flyleaf Books) was all-but-snowed out, but a few stalwart friends and family members braved the snowy conditions to attend the reading and drink bourbon whiskey.

The major highlight of that improbable book tour was the 2015 American Bookseller Association’s Winter Institute in Asheville, NC. We stayed at the renowned Grove Park Inn, which was just down the way from Highland Hospital, where Zelda Fitzgerald spent her last years in a psychiatric facility. On the eve of the literary conference, I sat at the hotel’s historic hotel bar, where F. Scott Fitzgerald had conducted one of his last and most notorious interviews. The author of The Great Gatsby had come to the Grove Park Inn in 1935 and 1936 to be near Zelda and escape his own demons. He rented one room to sleep in, another for writing, and tried to curb his gin-addiction with a “beer cure” of fifty glasses of beer per day.

It didn’t work. Fitzgerald turned forty at the hotel and hurt his shoulder when he awkwardly dove into the hotel pool. He also slipped in the bathroom and was found on the floor by his nurse. He agreed to a New York Post interview in hopes of salvaging his reputation, but the interview backfired, cementing his tragic legacy. When the reporter asked Fitzgerald about the celebrity authors of the Jazz Age, Fitzgerald responded:

"Why should I bother myself about them? Haven't I enough worries of my own? You know as well as I do what has happened to them. Some became brokers and threw themselves out of windows. Others became bankers and shot themselves […] and a few became successful authors.” His face twitched. "Successful authors!" he cried. "Oh, my God, successful authors!" He stumbled over to the highboy and poured himself another drink.1

I didn’t know anything about Zelda or Scott Fitzgerald’s story at the time. All I knew was, I was representing my novel at a literary conference; in my young mind, this was the very definition of success. On the day of the conference, I entered a large, lavish room with red carpeted flooring and dozens of fold-out tables, one of which had stacks of Slim and The Beast primed for signing. For the next few hours, I sat and watched literary giants meet their fans, and while I had none to speak of, I did sign a few copies of my book, which was one of the most validating experiences of my literary life. Afterwards, I ate dinner with booksellers and publishers from around the country, some of whom expressed doubt about the success of a literary fiction novel about basketball, male intimacy, and North Carolina. But as far as I was concerned, whatever happened afterwards was a bonus … my name was on a bookshelf, fiction readers’ preferences for fantasy and YA be damned.

The hoopla came and went. I returned to Paris to resume my teaching job and was told to hunker down and educate myself in social media, but I neither had the time nor patience for blogging and Twitter. I also had to pay rent, and even with my publisher’s alternative model and generous percentage for authors, it was impossible to make a living from subsequent book sales alone.2 After spending a year on self-promotion and digital marketing strategies just to get Slim and The Beast published, I didn’t have the energy nor desire to brand myself once again.

I am a fiction writer because in part, I prefer escaping into fictional worlds to having to constantly face reality. A new sentence for a novel soon crept into my mind, a story that had begun with my master’s program in London:

When the sirens began, the professor was sitting at the Astoria Café.

I was ready to write again, and for myself. What I’d learned from publishing Slim and The Beast was that not even a print-run of 1,000+ copies, book readings in Paris, North Carolina, and New York City, and some small press attention guarantees you anything other than an ego-boost and a brief reprieve from imposter-syndrome. I was proud of Slim and The Beast in the same way a young parent is proud of their infant’s first drawing on the fridge. This didn’t mean I didn’t like the book, but it did mean it was of the past now, and I had moved on. If I could coat Slim and The Beast in a cube of amber, like a once-living insect, I would. I’m happy to have written it, but precisely because it’s out in the world, it no longer feels so much a part of me.

Life has always been most generous to me when my bank account is at its lowest and my general sense of optimism is teetering on empty. Just a few weeks later, my publishing debut had become old news, and all that remained was the dreaded question, “so, what’s next?”

I was back in Paris teaching English for lousy pay, living in a cramped 14m2 apartment and navigating the growing complexities of a co-dependent relationship. Needing to shake things up to feel inspired and escape in a different way, I began singing and playing blues and folk music with a friend I’d met on a Parisian basketball court. I also quit my teaching job and found a writing gig where, for exactly three weeks, I moonlighted as a click-bait-style journalist until I realized that writing eight-hours a day about digital trends and technology was the easiest way to guarantee I never wrote again.

While I bit my fingernails about quitting a well-paid job after only three-weeks in, my publisher contacted me and said that they wanted me to be their representative at a literary conference in California. Their first choice had fallen ill after being bitten by an unnamed insect, and if I could fly out to California, I would be the publisher’s representative. Without hesitating, I used this as an excuse to leave my writing gig the very next day, only to find out, a few days later, that the journey to California wasn’t going to work out in the end.

The bohemian gods were kind to me in a different way. Out of the blue, a friend told me about an acquaintance who needed a part-time, glorified receptionist at their financial offices in Paris. It paid twice what I’d been making as an English teacher. For the next three years, I was a secretary at Deutsche Boerse’s Paris office, where I learned how to tie a tie, manage a monthly budget, transfer phone calls, smile at VIP guests, organize and throw lavish parties with company budgets (the highlight was an epic evening at The Ritz), and wrote multiple drafts of a novel set in Nazi Occupied Poland about three characters: Viktor, a disillusioned academic; Elsa, a young secretary seeking purpose in life; and Carl, Elsa’s estranged fiancée, an alcoholic policeman obsessed with returning to the past.

I was writing well, but not because I was happy. The fractures in my 4-year relationship soon became too significant to bear, and we decided to end the relationship before it became more toxic. And so, with a shoddy draft of a new novel that still needed a voice of conviction, heartbroken and in need of a major life change, I was offered an adjunct gig as a creative writing teacher at the Sorbonne, which partly inspired me to enrol in an MFA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts. This time, I was going to do academia the way I wanted: my goal was to find a new voice, mentors, and a literary community.

I saved enough money to be able to rough it for a few months, and in the spring of 2018, at thirty years old, I quit my secretarial job and moved to New Orleans to play indie/folk music with my band-mate and twin brother. We decided to call the band Slim and The Beast. The story of our musical journey began in earnest with those three months in New Orleans, where I learned about backyard crawfish boils and dance parties at Vaughan’s and what happens when you take a heavy dose of LSD right before participating in a massive parade (hint: you run towards nature and/or quiet), but that story is one for another time.

“And then,” I gloss over the last few years, “my world changed irrevocably in March, 2020.” It’s getting late now, and the living room is crowded, and I’ve been talking to you about myself for long enough.

We give up our couch seats and go to the kitchen to smoke a spliff. You lean out of the window to take in the late summer breeze.

“One last question,” you exhale. “You said your world changed irrevocably in March, 2020. But the entire world changed. So what do you mean?”

“Long story short, on Leap Day, 2020, I met an American photographer in a bar. At first, it was an artistic, platonic connection. She returned to the USA a few days later, just before the world shut down. Over the next five months, we fell in love over text messages and phone calls, road-tripped across the locked-down American northeast to see if the love was real, had a 10-person wedding in her parents’ backyard, with another 120 loved ones on Zoom, and a year after meeting each other, we were living in Paris together.”

“That’s quite the happy ending to the first twelve years in Paris,” you say as you reach into the refrigerator for two cold beers. You pop off the bottle caps with a lighter. “Or more like a happy new beginning.”

“Exactly,” I say. Our bottles clink. “But enough about my story. Tell me something about you.”

I was lucky if I made $3 dollars per book sale. To this day, approximately 1,200 copies have been sold, which means I’ve made about the same money on Substack in five months as I did in five years with a published novel. Given my experience with publishing, I’m flirting with the idea of self-publishing my third novel and printing it for my annual subscribers of this community.

A cautionary tale, but an inspirational one also. The only function of the writer is to write: money, fame etc are by-products, and must never be an aim. Once one accepts this and adjusts one's priorities accordingly, there is , at least in my own case, a sense of release and freedom. Keep up the good work.

This series is beautiful Samuel.