Of Politics & Prose (Part I)

discussing Nazism, humanity & Squid Game w/ a legendary DC bookstore

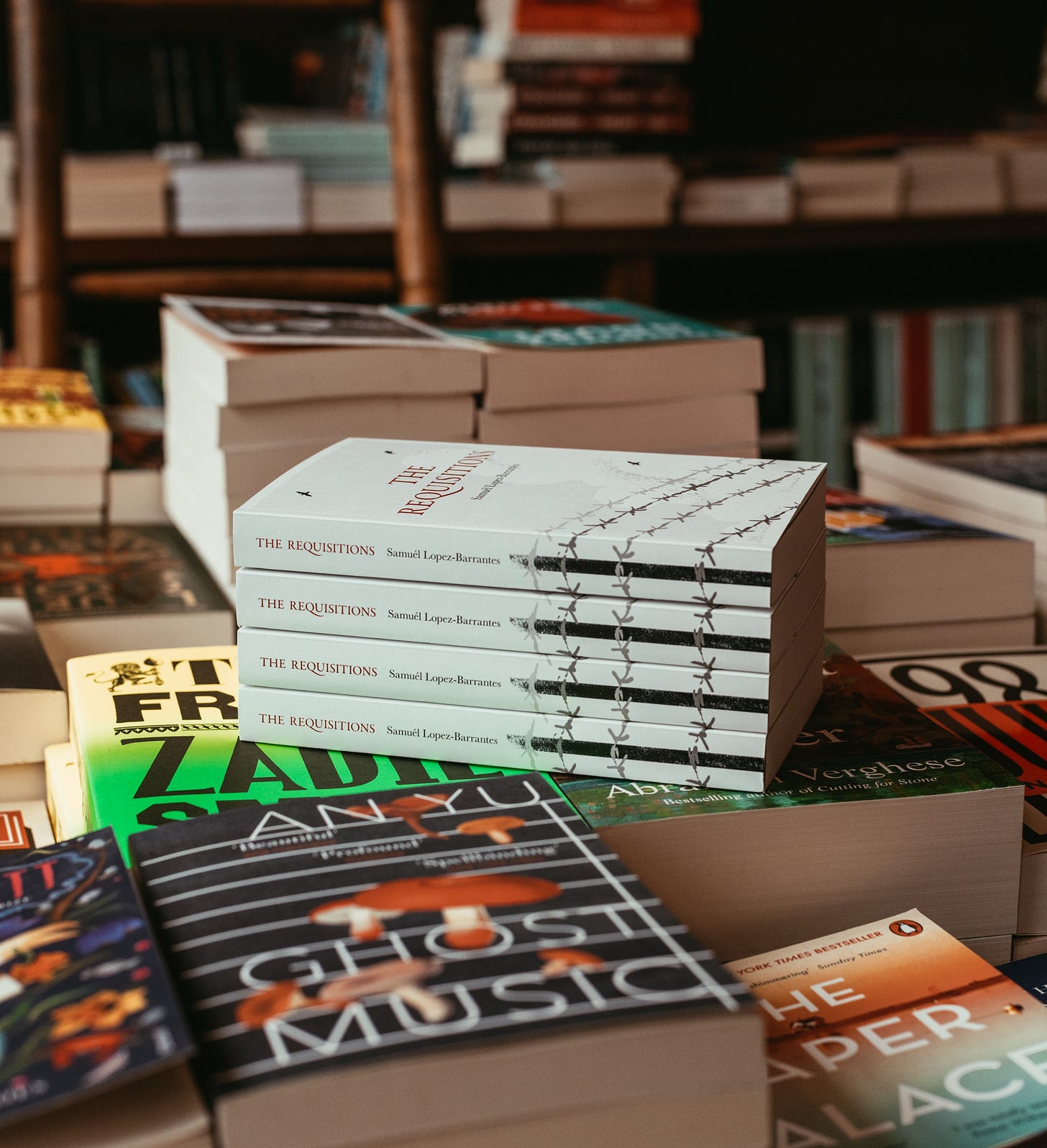

This is Part I of an abridged conversation with Politics & Prose (Washington D.C.) about The Requisitions, my latest novel about history, memory, and the Nazi occupation of Poland. Big thanks to Bob and Susan for inviting me to the bookstore, and

for choosing The Requisitions as part of her online course, Fighting Fascism: Three Novels and a Guide to Resistance.In Part One, I discuss Nazism, the humanness of hope and cruelty, and what I think about the success of Squid Game. Part Two (next week) will be partially-paywalled, as it has major spoilers, covers the narrative structure of The Requisitions, and it will be the first time I speak about the “controversial” ending.1

Q: It isn’t said enough that it wasn't just the Nazis who killed. In Ukraine and Poland especially, many locals killed and hunted their fellow human beings in the forest—and then they went back, and they did it again and again. The Nazis often used the local populations because their regular soldiers couldn’t take it, and the world hasn’t really understood or remembered that it wasn’t just the Nazis who committed genocide.

That's an important point. People also often forget that when we’re discussing the Nazi genocide, we’re talking about eleven million human beings. It was a different systematic policy of genocide for the six million Jewish victims of the Holocaust (which is a term usually reserved for Jewish victims), but the Nazis systematically murdered another 5 million human beings, particularly Poles and Russians, which many people forget.

In The Requisitions, Martin represents one of those smaller groups of victims (gay men), and part of the challenge of writing a book about the Nazi genocide is that it’s such a vast subject. There are so many ways to write about it, and there's no real way to write about it honestly comprehensively because whatever you do, you're going to be confronted with other stories—stories that each year are illuminated, stories which nobody has ever heard of before. And it’s the scale of it which … there’s a reason why World War Two remains the most read and studied subject in human history, and it's because many, many tens of millions of people participated in systems that also resulted in the genocide—or at the very least paid lip service to a system that was taken advantage of by fascist leaders.

And the pendulum is swinging. The cycle is back. It took me a decade to finish The Requisitions, and I had already been studying the Nazi genocide for a decade, so I can't say I was surprised or have been surprised by what's happening in the world, particularly in the USA.

My dad fled Spain, a fascist country, and, lo and behold, I left the USA before it became fascist. But I would say that the writing was on the wall even in 2009/2010 … I could feel this splitting of humanity, this Us versus Them binary thinking. And it’s scary because when you feel like you are on the right side of history, there's only one thing to do with the other side of it, and that's what disturbed me most studying the Nazi genocide: the conviction (which is from the Latin term to convince someone of something), a desire to constantly convince others of one's righteousness. That's a scary thing.

SPOILER Q: The passing of time is an essential idea in The Requisitions. You say remembering is like stopping time, and when Viktor is being tortured, it’s vital for him that he knows what time it is.

That torture section is challenging to read (and was very hard to write). The chapter is based on a book by a Belgian author named Jean Améry, who survived torture by the Gestapo. He wrote a collection called At the Mind’s Limits about how to intellectualize—and is it even possible to intellectualize?—the nature of torture and brutality. If his entire life was to train to understand the mind and how to perceive existence, he wondered, could he use his intellect to better survive?

The jury’s out on that. Jean Améry ended up taking his own life (as did many other survivors, including the author Primo Levi), and of course, I don't know how one could make peace with such brutality. It was a challenge to write that section but also to put myself in a position of attempting to locate the possibility of hope in such a scenario. As far as whether or not there’s hope at the end of the book, I have my ideas. As Americans United Statesians, we believe in happy endings as an ideal; as a European, I prefer to think of them as a possibility.

Q: What do you think we’ve forgotten in 2025 that we must remember?

My knee-jerk reaction is reaching across the aisle (however you define that). I find this era is very fragmented because of technology, which connects us, like we're doing now, but which also confines us to our homes. Grocery deliveries mean you don't have to go to the store, which means you don't necessarily meet the grocer who might be very different than you.

I enjoy going to the bar and the terrace to meet people in Paris. Post-Covid, however, and especially in places where people have to drive everywhere, folks don't interact with each other like they used to. And the scariest thing for me is to recognize how many people voted for someone who is a self-described authoritarian, and [most people] don’t talk to anyone who voted for that guy, or vice versa. That, for me, is what’s scary. I don't know if it's an unwillingness, an inability, or part of the design of our society not to interact with folks who are not like us … but I know how historians and people who lived through fascist eras talk about them, and it is very rarely the most sadistic, monstrous types that are the problem—the cliché is the people who keep their head down and don't say anything.

It’s a hard thing to have a dialogue with people who don’t believe in the same kind of humanity we do—that is not easy—but that’s also the point the duty of being educated, and I have a suspicion that the conversations at the cafe or pub or grocery store immediately cut through that tension. Dialoguing face-to-face is very different than viewing the world through the key-hole of the Internet.

In times of spiritual disillusionment, we start distrusting each other because there's not a unifying thing to connect us, which leads to tribalism and … I mean, I grew up in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The shade of blue you wear can get you punched in the face. Which is a hilarious concept to me. “Duke Blue” versus “Carolina Blue” is a fundamental philosophical difference for some people—even in their sixties, their faces get red, you know, when they start talking about it, so you’ve got to reach across the aisle. Speak to the fans of your rival—that’s what I think we need to remember.

Q: What are your thoughts about the recent success of Squid Game?

What's ironic about Squid Game is the show’s writer, Hwang Dong-hyuk, was a struggling screenwriter who ended up selling his computer upon which he’d written Squid Game to pay for expenses. Years later, Dong-hyuk became a millionaire when, lo and behold, his depiction of a hyper-capitalist country consumed by greed and power was finally picked up. Today, the show is a dystopian reference point for the entire globe.

Season 1 is a valuable commentary on the Zero-Sum nature of hyper-capitalist consumerist greed. I don't think capitalism is the problem; its implementation is, and Squid Game certainly raises those questions. We all want to win are told to want to win the Nobel Prize and be the best of everything and, reach the top of the pyramid and, have our own TV shows, become president of the USA … this is the same narrative we've been taught for decades—that we all should be at the very top of the pyramid—but the pyramid is the problem, I think. So here's to circles, not pyramids. And even Squid Game, as a success story, perpetuates the issue (do yourself a favor and avoid watching Season 2). We’ve all been sold bought into this myth that becoming rich and famous is the goal, so I'm not particularly shocked by what's happening in the USA … what surprises me most is that so many people still act surprised by the absurdities and cruelties happening worldwide.

Q: Yes. At one point, there’s a line in your book about how we shouldn’t be shocked by all the cruelty happening …

Yeah. And that’s part of why there are really cruel scenes in The Requisitions. We watch Squid Game and other films filled with extreme brutality, and then some people pretend to act shocked when they see a nipple on the television. So, while I understand the challenge of reading the torture scene, we also witness gore in Hollywood movies and just call it a movie … I think we're totally desensitized in some formats and remain shocked in others, but this is no longer something we can afford. The level of outrage has become really toxic … we’ve got to look at the cruelty in the face and confront it.

Note about the audio recording: out of respect for privacy, I’ve removed the participants’ voices. The above written text is also slightly different than the audio recording, because I am my own PR team and something something creative license.

Fabulous class with you! The Requisitions so beautifully written, poetic in parts, well researched history entwined with philosophy - loved that your key characters represent different, important philosophical threads, Victor for our search for meaning from Victor Frankl and more, not to do too many spoilers... Your positive, informed view of the world a thought provoking bright light in our class. The Requisitions highly recommended as history, as literature, as timely commentary. Thank you for all!

Wonderful, Samuél, thank you for this recap of some of the highlights from your visit to my class. I'll share this with the class participants when we meet for the last time tomorrow. It was wonderful to have the opportunity to discuss your book with you. And even better that you have now captured these highlights and shared them with others--and also given us a way to hold onto the experience for a bit longer than just our memories would allow.