1

I had a surrealist phase. I suspect many writers do.

As someone who grew up in the nineties twilight of postmodernism (here’s looking at you, Seinfeld/Dave Chappelle/David Foster Wallace), for a time I was convinced that the more absurd and phallic cerebral my work became, the more I could approximate the sur-realities usually reserved for the depressed, drunken, or insane. And so, after months of telling myself that I had to see the surrealist exhibit at Centre Pompidou for reasons that escaped me until the very last hours of the exhibit, on a rainy Monday afternoon in the depths of a Parisian winter, I found myself riding a crowded escalator to the sixth floor of the museum.

2

Living in Paris affords people like me the aspirational illusion that because I’m surrounded by culture, I’m thus imbued with its wisdom. But just because we exist in a space doesn’t mean the space exists within us, especially when that space is an overcrowded room filled with pop art cultured consumers.

The word consumption used to refer to the wasting disease known as tuberculosis, which infected (and killed1) many artists before surrealism came on the scene. The poet Guillaume Apollinaire coined the term surrealism at the end of World War One, a calamity so horrific that many who witnessed the brutality lost their minds (Apollinaire fought in the trenches, had a piece of shrapnel forever lodged in his head, and died in 1918 of the Great Flu ... what a time to be alive!).

In the face of such stark brutality, a young psychiatrist working with traumatized soldiers realized that some war veterans could sublimate the horrors they’d witnessed by imagining the battlefield was nothing more than a spectacle. Soon after, André Breton had a revelation: when faced with the horror incomprehensibility of war reality, the mind can transport itself elsewhere—and thus surrealism was born.

Dare my callous subconscious draw a connection between trench warfare and a crowded Pompidou? No. But this is an essai, after all, nothing more than an attempt, an experiment, and like it or not, my brain (and so yours too, dear reader) is once again making a connection between the irretrievable past and the eternally present moment.

3

According to the tax man, I’ve lived in Paris since 2010. Given my luck to live in what people far wiser than me have long deemed the most beautiful city in the world, I tend to witness the most Instagrammed commercialized events in this city float by like crowded tourist boats on the Seine. Those boats can be fun, of course—I’m simply a tourist when I go anywhere else—but one of the luxuries of living in Paris is having an inkling when braving the long lines of Tik-Tokking hordes is worth the wait (my experience at the 2023 Rothko exhibit comes to mind, as do the 2024 Olympic opening ceremonies and, most recently, ice skating at the Grand Palais, which was decidedly worth the wait).

After witnessing a huffy, entitled white woman shoulder charge her way through the beginning of the exhibition, I waded through dozens of NPCs, all trying to capture a zoomed-in photo of a famous Salvador Dali painting without including the shadows of their compatriots’ silhouettes. Once I got past the eddies of iPhone-wielding jellyfish museumgoers, the types that tend to only ever pause in front of the most famous consumable works of art, I found reprieve in front of a haunting collection of nighttime photography by Brassaï. Soon enough, however, I had to cede the space to one of those types of men—why are they always men?—who believe the essence of museum art can be captured through a comically large digital camera lens and/or a live stream with a camcorder.

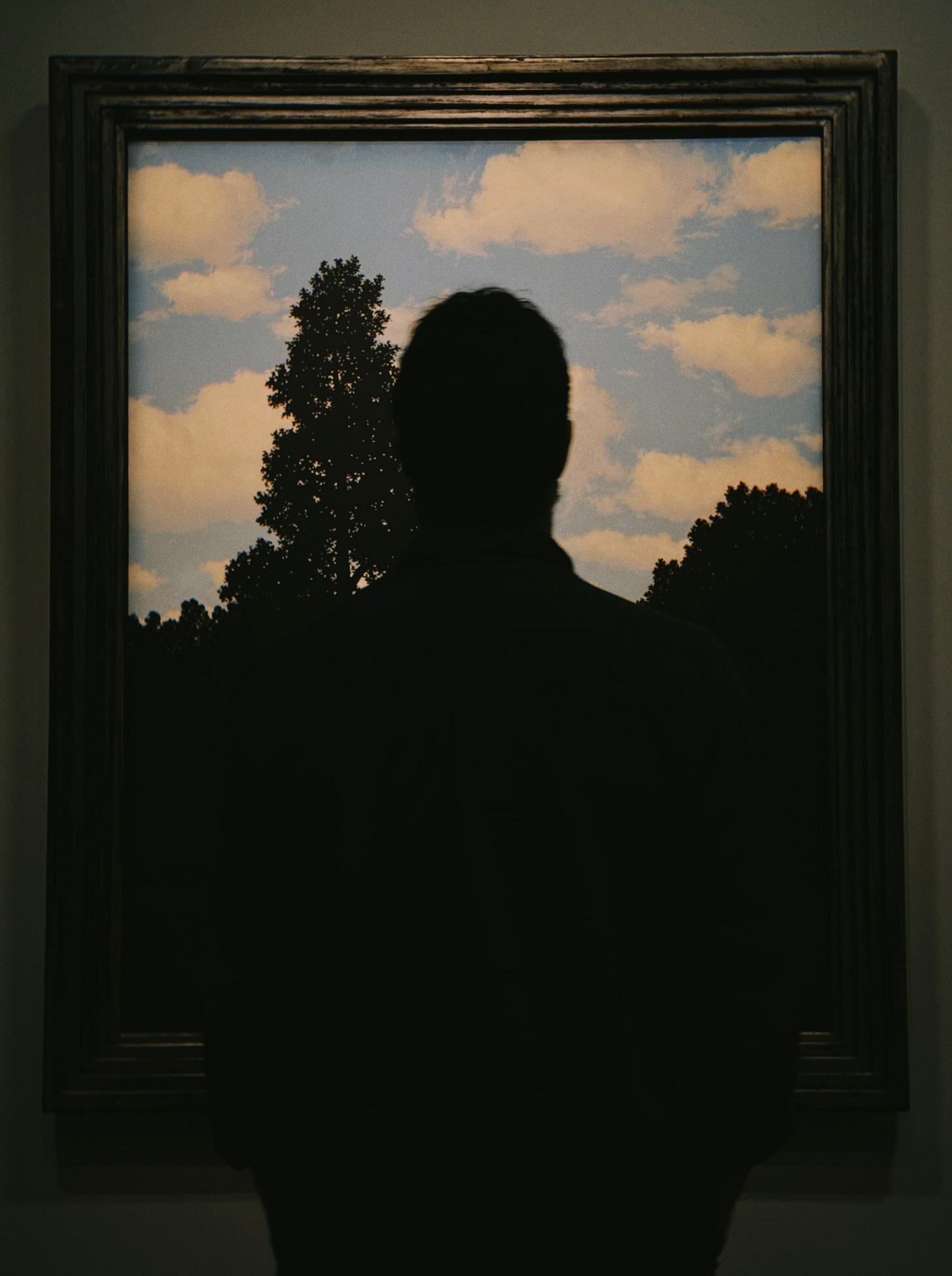

Moving onwards, I found what I didn’t know I’d been searching for: a quiet section that held space for René Magritte’s “Empire of Light,” which juxtaposes a suburban street at night with a bright blue sky above.

Surrealist interlude: instead of sharing a photo of the painting, write a stream-of-consciousness describing it:

Imagine a sunny day on a familiar street that reminds you of home. The air is thick enough to be summer, but it’s still just spring. Now, picture a solar eclipse, and when the moon blocks your view of the sun, cut that suburban street in half into day and night. Both lightness and darkness reign supreme in the kingdom of heaven and hell existence, but you know better than that, don’t you? Good and Evil don’t exist.

Further onwards, I watched a pensive elderly man with a cane survey Miró’s “Constellations: Morning Star” before he was bonked by an objectionable woman wearing an oversized backpack and holding an all-inclusive robot in front of her face—“Such is human nature,” Mary Shelly wrote in one of the first post-apocalyptic books ever written, “that beauty and deformity are often closely linked.”2

4

If Magritte’s painting reminded me of the duality that formed the core of my latest novel, The Requisitions3, Remedios Varo’s “Papilla Estelar” confirmed what happens when feminine energy is “permitted” to enter a male-dominated space (many surrealists, most notably Andre Breton, AKA the Pope of Surrealism, were famously chauvinistic; in my mind, Varo, an artist who had ovaries, fused the surrealist ethos of dream and reality far better than most of her penis-obsessed contemporaries).

The title of Remedios Varo’s “Papilla Estelar” translates as “porridge for the stars” or “stellar pablum,” which, according to my computer’s dictionary, refers to intellectual baby food (“bland or insipid intellectual fair, entertainment; pap”). This felt particularly appropriate given the proximity of Varo’s paintings to many of her male counterparts’ more celebrated commercialized phallic obsessions: in “Papilla Estelar,” a tired-looking woman operates a hand-cranked mill to grind the cosmos into celestial porridge, feeding ground-up stardust to a captive moon.

As I stood there contemplating Varos’ brushstrokes and this male-dominated world’s continued imprisonment of the moon feminine, a young woman approached the painting, covered her mouth with her hands, sighed deeply, closed her eyes in the way one does when witnessing primordial wisdom, and remained transfixed.

Eager to remember the thought before I exited the exhibit, I jotted down the following words in my notebook:

Who are we to keep the moon locked in her cage, force-feeding her our hungry vision of the cosmos?

Or, to put it differently, exiting the museum’s main hall, what is this celestial all too human desire to consume and be consumed? To capture an unreal image of a masterpiece that can only ever be witnessed in the flesh? To imprison a never-to-be-watched-again video in the robot in our pocket, grinding up the lustrous magic of the museum instead of basking in the moonglow of the eternally present moment?

Anton Chekhov, Franz Kafka, and multiple members of the Brontë family come to mind.

Mary Shelley, The Last Man, 1826: “But in the country, among the scattered farm-houses, in lone cottages, in fields, and barns, tragedies were acted harrowing to the soul, unseen, unheard, unnoticed. Medical aid was less easily procured, food was more difficult to obtain, and human beings, unwithheld by shame, for they were unbeheld of their fellows, ventured on deeds of greater wickedness, or gave way more readily to their abject fears. Deeds of heroism also occurred, whose very mention swells the heart and brings tears into the eyes. Such is human nature, that beauty and deformity are often closely linked.

The Midwest Book Review: “The elements of history, memory, and love are intertwined in "The Requisitions", an historical metafiction set in Nazi-occupied Poland. Original, deftly crafted, memorable, and with a distinctive storytelling style, author Samuél Lopez-Barrantes has elevated The Requisitions to an impressive level of literary excellence from start to finish.”

“Who are we to keep the moon locked in her cage, force-feeding her our hungry vision of the cosmos?”

Thank you for your thoughtful repose on the surrealness of these *pop* moments.

Beautiful. What a profound visual metaphor. As for your experience overall, it reminds me of being at the Getty - the hump of humanity around Van Gogh's Irises made it impossible to see, while The Milliners by Degas hung quietly in the corner--to me, a far more brilliant and moving work. Of course, the Getty is not the Pompidou! Same type of crowds though, it seems.