“I must hold in balance the sense of the futility of effort and the sense of the necessity to struggle; the conviction of the inevitability of failure and still the determination to “succeed”—and, more than these, the contradiction between the dead hand of the past and the high intentions of the future.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald, “The Crack-Up” (1936)

It’s been ten months

since I published my second novel and there’s an image that keeps visiting me just before I fall asleep:

I’m a farmer at a kitchen window looking out at fallow fields. The callouses on my hands have softened. The winter fog is lifting. Sunbeams pierce the clouds and the earth begins to percolate. It’s time to get back to the land.

An easy way for a novelist to justify a prolonged period of not writing the next one is to believe what the industry dictates: the most enduring importance of writing books is selling them.

I’ve been a novelist for fifteen years and have been an author (i.e., published) for almost ten. If there’s one thing I’ve learned over my slow and steady writing life, it’s that there are few things more destructive to my novelist-self than thinking what’s most important about writing a novel isn’t the writing, the editing, or even the publishing, but marketing a book my author-self into oblivion instead of getting to work on the next book.

This essay is not, however, an excoriation of authordom, for I’ve learned much since publishing The Requisitions. I’ve built a modest literary community here on Substack,1 have diligently contacted bookstores and reviewers, have joined the Independent Book Publishers’ Association, and, most recently, have galivanted as a novelist/author/publisher2 at the 2024 Frankfurt Book Fair, where my wife and I, the proud founders of Paris-based Kingdom Anywhere Publishing, schmoozed with kind literary agents and jaded foreign rights scouts in a swanky hotel bar in the heart of a once-firebombed-city.

It's all been great, and necessary, and invigorating, and yet I keep returning to that image of the farmer at the window. Thankfully, a few nights ago, unable to sleep on the eve of the Frankfurt Buchmesse, wondering how much more time I should spend trying to convince people that The Requisitions is not only worth reading but also worthy of wider recognition, I began reading an essay a cautionary tale by F. Scott Fitzgerald called “The Crack-Up,” which discusses the difference dissonance between being an author selling books and a novelist writing them.

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise.”

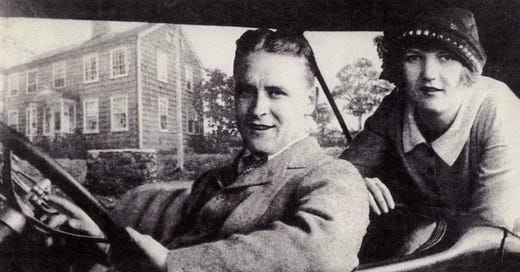

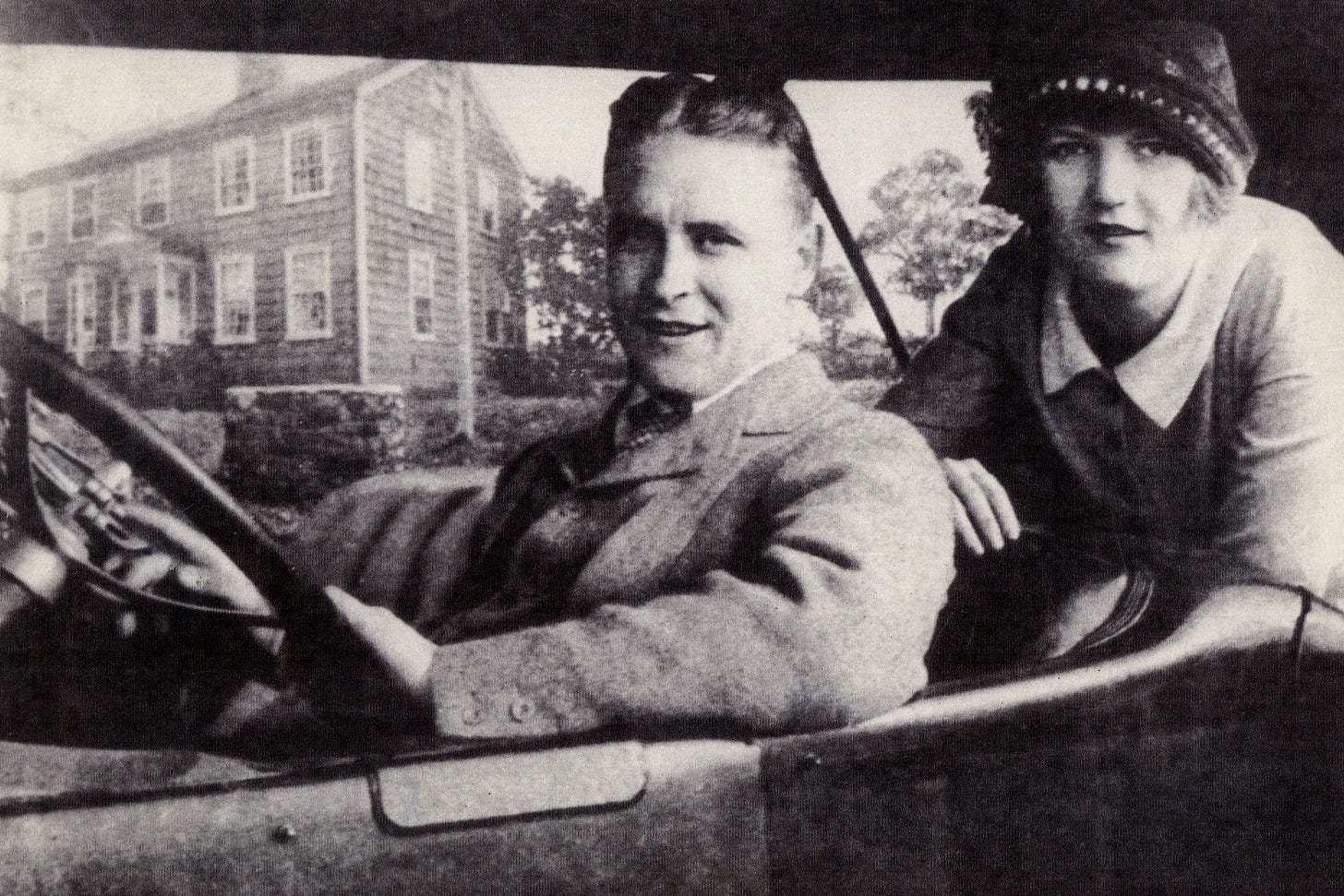

“The Crack-Up” (1936) was written during the Golden Age of Hollywood, a decidedly dismal age for F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Sayre. The cults of personality that had come to caricaturize them individually (Scott, a novelist Princeton student obsessed with wealth power; Zelda, a southern artist belle preoccupied with attention celebrity) turned them into one of the most co-dependent and toxic tales in US history.

The story of the Fitzgeralds is as glamorous as it is tragic precisely because it represents the effervescence of an era that began in the Jazz Age and ended in the Great Depression. It is an all-American United Statesian Cliché, an enduring cautionary tale about the existential price artists pay for pursuing wealth power and fame ego as ends in themselves.

Beware the Beginnings

F. Scott Fitzgerald was raised in a middle-class family that constantly wanted more never thought it had enough. As such, Scott’s family instilled in him an obsession with “making it,” for according to the family lore, his ancestors had once “made it,” too.

In the midwestern USA in the early twentieth century, “making it” was a puritanical euphemism for good old-fashioned materialism—“getting the job,” “getting the girl,” “getting famous” … in other words, objectification of the idea of the self (and others) via the acquirement of objects and fame of which the Jay Gatsbys and Daisy Buchanans of the real world could be proud.

Before falling in love with Zelda Sayre, Scott pined for Ginevra King, a Chicago vixen one of the wealthiest American heiresses of her time. But alas, Poor Scott was from a lower class. In 1917, Ms. King broke off the relationship with Scott and married a man named Bill, a wealthy banker’s son. Heartbroken Emasculated, Scott dropped out of Princeton, joined the Army, and began writing a manuscript called The Romantic Egotist about love, greed, and heartbreak as he prepared to fight in the Great War.

During his military training in Alabama, however, Scott met the rich beautiful daughter of a wealthy powerful judge from Montgomery, Zelda Sayre, an intellectual debutante who knew how to party, dance, and hold deep conversation. Zelda fell for the young Yankee on one condition: before they got married, Scott would have to get rich and fast, for in both Scott and Zelda’s worlds, The Man had to bring home the proverbial bacon.3

World War One ended on November 11, 1918, allowing Scott to move to New York City to seek his riches. But even back then—if you can believe it—life was hard for a novelist to earn a living, and Scott didn’t impress Zelda with his measly copywriting and advertising income. After receiving scores of rejection letters from literary magazines and an encouraging disappointing rejection of The Romantic Egotist from the famed Scriber’s editor Maxwell Perkins, Zelda broke off the engagement. Scott became suicidal and daily contemplated the weight of the revolver he kept in his pocket. Having been rejected twice by the women of his dreams and no longer able to envision a life as an author, Scott returned to Minnesota as an unaccomplished novelist and rewrote The Romantic Egotist with a different title.

The rest, as they say, is history. Scott’s updated novel, This Side of Paradise, became a literary phenomenon overnight, helping Scott “get the girl,” thus cementing him and Zelda as the celebrity couple of the Jazz Age.

The Crack-Up

“There was a rankling indignity, that to me had become almost an obsession, in seeing the power of the written word subordinated to another power, a more glittering, a grosser power …”

Anybody who has read Scott or Zelda’s writing knows the spiritual cost of pursuing fame and fortune as ends in themselves is a recipe for destruction.

In her only novel, Save Me the Waltz (1932), which she wrote from the confines of a psychiatric ward, Zelda Fitzgerald Sayre recounts the story of a wealthy American artist couple who moves to France and succumbs to years of mutually destructive partying, dishonest promiscuity, and insatiable hedonism.

Save Me the Waltz was published two years before Scott wrote his version of a picture-perfect romance gone wrong in his 1934 Tender is the Night. In typical chauvinist pathetic fashion, Scott accused Zelda of plagiarism even though she’d published her version two years earlier. Scott and Zelda’s relationship never recovered. Zelda spent most of the rest of her life in and out of mental asylums, while Scott moved to Hollywood to seek his riches in screenwriting (and other women).

The last pages of “The Crack-Up,” written in the depths of Scott’s sorrow,4 are proof of the novelist’s realization that he wasted years in pursuit of the wrong thing:

“I have now at least become a writer only. The man I had persistently tried to be became such a burden that I have “cut him loose.”

During the last few precious months of sobriety before his death, the author novelist finally got back to the land to work on what mattered most, a new book entitled The Last Tycoon (it was never finished) before alcoholism and depression a heart attack finally killed the once-acclaimed author F. Scott Fitzgerald at just forty-four years old.

Zelda Fitzgerald Sayre’s ending was no less tragic. At forty-seven years old (1948), she was seen as a caricature of a forgotten age, having transitioned from “the daughter of a judge” to “the wife of a famous author,” further reduced and objectified into an institutionalized shell of a human being talented artist who died in a hospital fire while sedated.

In the penultimate paragraph of “The Crack-Up,” Fitzgerald confesses:

I think also that in an adult the desire to be finer in grain than you are, a ‘constant striving’ (as those people say who gain their bread by saying it) only adds to this unhappiness in the end—that end that comes to our youth and hope … so in my case there is a price to pay.

After almost ten months of striving to present myself as the author of The Requisitions, “The Crack-Up” reminds this farmer to return to the land. While my experience at the 2024 Frankfurt Book Fair felt like a grand success for reasons neither big nor entirely small, Fitzgerald’s words remind me that an author shooting for the stars is only human, but a novelist remaining earthbound might be divine.

Paying subscribers now have access to a monthly literary lecture/conversation via Zoom. The subject of the discussion on November 21 @ 7pm CET (1pm EST / 10 am PST) will be, you guessed it! The Fitzgeralds in France. More on this soon.

When Zelda was asked to offer up a recipe for a collection called Favorite Recipes of Famous Women, she responded with this: “See if there is any bacon, and if there is, ask the cook which pan to fry it in. Then ask if there are any eggs, and if so try and persuade the cook to poach two of them. It is better not to attempt toast, as it burns very easily. Also, in the case of bacon, do not turn the fire too high, or you will have to get out of the house for a week. Serve preferably on china plates, though gold or wood will do if handy.”

Further proof: a devastating 1936 New York Post article about Fitzgerald’s crack-up, “The Other Side of Paradise, Scott Fitzgerald, 40, Engulfed in Despair"

Nice work, Samuél … and delighted that you will be servicing the tractor and starting the ploughing. Seeds to be sown before the harvest and all that jazz. I get that a novel is the thing … BUT … I can’t be the only reader who would relish a book of essays. You have much to say … and you say it well. If only you knew a small publishing house who would take a punt on a promising writer with a couple of excellent novels under his belt. Onwards, friend … the best way to be a writer is to ‘just write, right’!

Will be interesting to see what you write about next. I brought Kindle version of The Requisitions. I like how you define the word with all it's meanings because that advises how the story can be viewed. Great, the unique it's put together.