The Origins of Fascism (Part II)

Power in Pleasure: Benito Mussolini & Sigmund Freud's "pleasure principle"

This is the next chapter in a long-form essay about the origins of fascism. Read The Origins of Fascism Part I: A War to End All Wars & An Italian Disaster

“I cannot think of any need in childhood as strong as the need for a father’s protection […] The origin of the religious attitude can be traced in clear outlines as far as the feeling of infantile helplessness.”

Sigmund Freud, Das Unbehagen in der Kultur (Civilization and Its Discontents, 1930

You could be forgiven for assuming Freud’s entire philosophy is passé because he conflated psychoanalytic theory with cultural theory, but such is the nature of philosophy—it’s only ever devised by human beings—and as the old adage goes, when you assume, you make an ass out of you and me.

“Life, as we find it, is too hard for us,” Freud laments. “It brings us too many pains, disappointments and impossible tasks. In order to bear it we cannot dispense with palliative measures.”1 Much like Friedrich Nietzsche, an undeniable predecessor in psychoanalytic philosophy, many people find it fashionable to disregard Sigmund Freud because of his outdated ideas about sex and sexuality, but a) he was born 168 years ago and b) just like Nietzsche, he fully acknowledged the limits of his own thinking. “I have always confined myself to the ground floor and basement of the edifice [called humanity],” Freud admitted, forever curious about elevating his theory of human nature up from “the ground floor.”

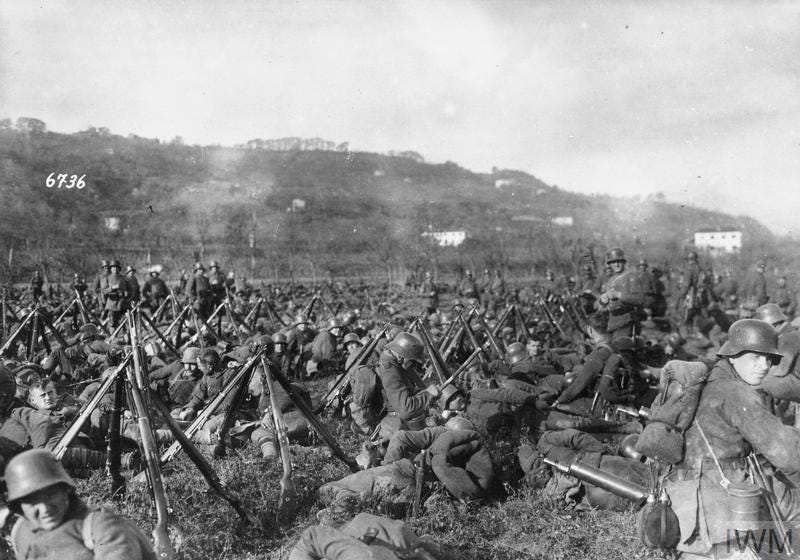

In 1920, two years after the Italian Army claimed victory at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, signaling the beginning of the end of the Great War, Freud published Beyond the Pleasure Principle in an attempt to update his previous theories that the human condition is primarily based on pleasure-seeking and the avoidance of pain.

One of the first mentions of a deeper, more primordial aspect of Freud’s theory of the human condition can be found in The Ego and the Id (1923): "We have reckoned as though there existed in the mind […] a displaceable energy, which is in itself neutral, but is able to join forces either with an erotic or with a destructive impulse.” In imagining this latent form of a distinctly human form of displaceable energy (as we’ll read in subsequent chapters, Viktor Frankl defined this as “meaning”), Freud developed the mystical notion of the death drive Thanatos and its eternal conflict with the life instinct Eros, a theory he created following the most destructive era in human history.

In 1920, the same year Beyond the Pleasure Principle was published, Freud buried his beloved daughter, Sophie (29 y/o), who’d contracted Spanish Flu while pregnant with her third child.2 “The undisguised brutality of our time is weighing heavily upon us,” Freud wrote in a letter to a friend. Just three years later, after a lifetime spent smoking battling various forms of mouth cancer, which affected his speech and forced him to wear a mouth prosthetic, Freud was diagnosed with jaw cancer in 1923, which ultimately killed him in 1939 after sixteen years of extreme discomfort.

No wonder, then, that in the latter stages of Freud’s life, he suggested three types of suffering define the human condition: 1) our own body and the inevitability of death, 2) the external world and its destructive forces, and 3) our relationship (or lack thereof) to other human beings.

So yes, while Freud’s philosophy lingered in the “basement of the edifice called [humanity],” existential malaise does not exist without external contexts. In his most accessible work, Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, Freud suggests that civilization itself is at the core of our discontent,3 which is why “we cannot dispense with palliative measures” to respond to the resulting state of our “infantile helplessness,” forever seek protection from the external world.

The Origins of Human Suffering The Origins of Fascism

1) Our own body and the inevitability of death (see: 560,000+ Italian soldiers killed, close to 1 million wounded, and let’s not even mention the Spanish Flu)

2) The external world and its destructive forces (see: WWI (i.e., poison gas, machine guns, tanks, bombers), the Bolshevik Revolution, etc.)

3) Our relation to other human beings (see: the end of empire as ideology and the emergence of new paradigms (particularly communism and fascism), which created discord across the world)

Enter Palliative Measures Il Duce

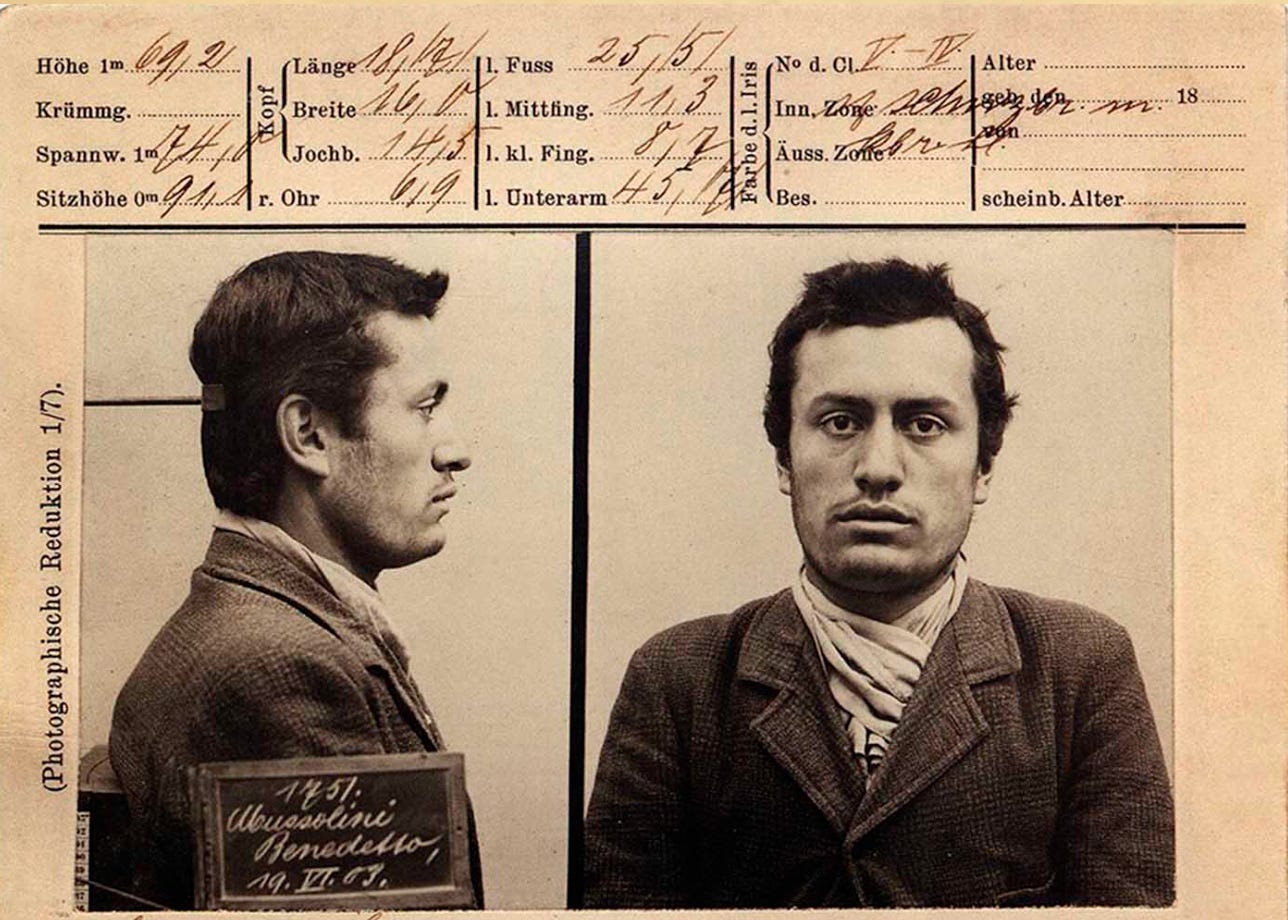

The right-wing fascist Benito Mussolini began his political career as a revolutionary socialist. If you don’t believe me, take a look at this 1903 mugshot taken in Switzerland, where Mussolini fled to avoid military service, began working for the Italian socialist movement, and was arrested after advocating for a violent general strike:

If you can believe accept it—yes, these are historical facts—Benito Mussolini began his political career as an anti-imperialist and anti-nationalist, a devoted member of the Partito Socialista Italiano (Italian Socialist Party) who attempted to enter left-wing politics, wrote against Italian involvement in World War One, and served as editor for the socialist Avanti newspaper from 1912-1915.

Considering what he became, these facts may seem surprising, but the mutant nature of fascism is essential to understanding its allure. Dynamism and political flexibility freed Mussolini from stagnancy, which allowed him to appeal to discordant social groups that existed on the fringes (sound familiar?) by invoking the notion of a classless, unified State. Another historical fact: fascism appeals to nationalists and socialists (Nazism = national socialism)—oxymoronic socialists, however, who believe socialist policies should apply to the in-group (see: favorable economic and social policies for only the most worthy powerful segments of the population).

While it might seem curious that the same man who wrote “There are only two fatherlands in the world: that of the exploited and that of the exploiters” in The Class Struggle (Lotta di Classe) in 1910, and while you may be surprised to learn that the man who campaigned as the “Lenin of Italy” in 1919 soon became one of the most brutal dictators in the world, fascism is an ideology based upon aggressive action and idealism, favoring the projection of power and dictation of meaning appeal to the primordial over a strict set of laws.

Malleability—flexibility, on account of a hammer—was one of Mussolini’s fundamental (and admitted) tactics: “Only maniacs never change. New facts can call for new positions."4 Following the disaster at Caporetto and the lamentable outcome for Italy after World War One, Mussolini’s confidant and philosopher king, the ultra-nationalist Giovanni Gentile, stated, “What [the Italian people] needed was not a platform of principles, but an idea which would indicate a goal and a road by which the goal could be reached.”5 In an era of spiritual disillusionment, Mussolini understood that Italians needed something new to believe in—an ethos connected to the state. But before meaning could be derived, the Freudian pleasure needed to be appeased, which is why, in the beginning, the first goal was to provide protection—against nihilism, against outsiders, against the supposed “enemies within,” and against anyone who expressed doubts about Italy’s unexamined history greatness.

The first supporters of Italian fascism (Fascism hereafter) were right-wing nationalists, disgruntled war veterans, and obstinate patriots who blamed the post-war losses on the Versailles Treaty (even though Italy was victorious, it lost territory after the war). Other early supporters were inspired by the ultra-nationalist occupation of the Free State of Fiume (1919-1924), an 11 square-mile city in modern-day Rijeka, Croatia, where disillusioned veterans found purpose in a unified state and chauvinist promises of a return to a proud, militaristic Italy.

By 1921, following the Biennio Rosso ( “two red years, ”1919-1920) of intense social conflict and thousands of industrial and rural strikes, Italian farmers, 500,000 of whom had received land during the war, were determined to keep their newfound property. Fearing communist collectivization, they were attracted to Fascism, which promised to protect their newly landed interests.6 Even after the political pendulum swing from far left (1919) to far right (1921), Mussolini’s Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF) only won 35 out of 535 parliamentary seats. But with growing ranks of Fascist thugs in the countryside and promises of reuniting Italy by appealing to the lower classes to protect against communism, support for Fascism rose steadily in rural Italy—the next step was to take it to the cities.

Those further up the totem pole of power—landowners and estate holders—also supported Fascism because it protected their gentrified values from labor unions and socialist policies. Finally, the upper-middle classes living in urban areas—technocrats, industrialists, and wealthy businessmen—supported the former socialist nationalist/socialist because Mussolini promised the emasculated masses that he would resolve all of Italy’s problems by returning the nation to an era of Roman glory.

If there was any group wary of Fascism, it was the political elite, but even they preferred a Fascist government to antiquated politics, infighting, and the prospect of communist revolution. Following Mussolini’s infamous declaration, “Either the government will be given to us, or we will seize it by marching on Rome,” he followed through with his promise, marching on Rome on October 28, 1922, alongside 30,000 Blackshirts7 while thousands of other angry men wearing black shirts Fascist uniforms occupied strategic governmental buildings throughout the country. Fearing civil war, the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III ceded power to Mussolini, who became prime minister and immediately began dismantling the judicial system … and so Italy’s long descent into madness began.

Next week, we bid adieu to Sigmund Freud’s ideas about infantile helplessness, moving beyond the pleasure principle to understand the strong-armed nature of Fascism. To do this, however, it’s necessary to make room for one of Sigmund Freud’s philosophical successors, Alfred Adler, a Freudian protégé who split from Freud’s Viennese Psychoanalytic Society in 1911 (Carl Jung followed suit in 1914) and began the Society for Individual Psychology in 1912, where he could deepen his unique theory, “the social feeling,” as a companion to his important psychoanalytic interpretation of the Nietzschean “will to power.”

The Origins of Fascism (Part III)

Mussolini’s paramilitary squads, Alfred Adler’s theory of the inferiority complex and the resulting will to power.

Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1989), 23.

Another of Freud’s grandchildren, Heinerle, also died three years later, but Freud’s letters to his loved ones following Sophie’s death are a beautiful insight into his suffering mind: https://www.freud-museum.at/en/blog-posts-details/articles/freud-spanish-flu-and-covid-19

The book’s original German title, Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, can be roughly translated as “the discomfort in the culture”; Freud also proposed “Unhappiness in Civilization” and “Man’s Discomfort in Civilization.”

Stephen J. Lee. “Dictatorship in Italy.” Ch. 4 in European Dictatorships 1918-1945, 3rd ed., 122-177 (London: Routledge, 2008), 130.

Giovanni Gentile, “The Philosophic Basis of Fascism,” Foreign Affairs 6, no. 2 (January 1928): 298, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20028606

Lee, “Dictatorship in Italy,” 129.

In fact, Mussolini did not participate in the March on Rome but rather joined the next day when the cameras were waiting—such is another valuable lesson in fascist politics: sell the fascist sizzle, not the steak.

Samuél, I am learning so much from this series. Can’t wait for part three. Certainly, there are parallels to our time - and in the US’s weird red-hat MAGA movement. Why must bad clothing choices be part of fascism?

Wonderful essay!

Disillusioned individuals strive for superiority and dominance to compensate for feelings of inferiority.

Mussolini's rhetoric and the fascist ideology became the method, ideology, and identity for individuals struggling with feelings of fragmentation and alienation. With the nation struggling with the aftermath of World War I and feeling a sense of diminished status on the world stage... this unfortunately created an environment for hate to thrive... as people wrongfully believed it to be their method of liberation