The Origins of Fascism (Part III)

Might is Right: The Inferiority Complex & Alfred Alfred’s “will to power”

Part I of this essay discussed how the Italian people paid a sobering price for victory in WWI (600,000 dead, 1.48 billion lire of war debt, mass unemployment, and substantial loss of territory), leading to vast disillusionment, political turmoil, fears of communist uprising, and a legitimate inability to envision the future.

Part II summarized how Benito Mussolini sought to unite the Italian people by appealing to the Freudian pleasure principle human desire to pursue pleasure and avoid suffering.

Part III is about Mussolini’s paramilitary squads, Alfred Adler’s theory of the inferiority complex, and the resulting will to power.

See below for Part IV.

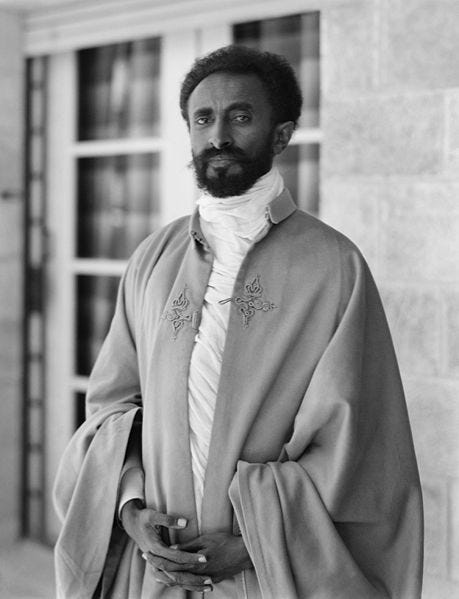

"It is us today. It will be you tomorrow” (1936)

Italian fascism (Fascism hereafter) was attractive to many in the early 1920s because it offered sublimation for what many believed to be a self-centered, hyper-individualistic era that overshadowed a sense of national spiritual identity.

Mussolini coopted the term fascismo, a “bundle of sticks,” to extoll the virtues of individualism within a collective context. By clearly defining an outgroup of “them” (i.e., communists, immigrants, trade unionists, but not Jews—the Fascist Party included Jewish members until Hitler made Mussolini his puppet in 1938), Mussolini was able to cultivate an ethnonationalist idea of “us” that appealed to the concept of Italian individualism while criticizing how unchecked international individualism could only result in spiritual decay.

During moments of economic and social crises (see: the USA today), moralistic groupthink and the pigeonholing of identity (however reductionist, essentialist, or problematic) is far easier than promoting critical thinking and pluralism across the political spectrum (in 2024, many liberals and conservatives alike remain convinced that there is a “right” and a “wrong” side, thus solidifying the belief in binary systems that can only end in a zero-sum game of “us” versus “them”).

Small wonder, then, that using a simplistic narrative of good vs. evil, Mussolini was also able to unite the proverbial peasants (lower classes), shopkeepers (middle classes) and aristocrats (the elites) beneath a singular idea of “the State”, thus sublimating the population’s suffering Freudian sense of “infantile helplessness”1 into a chauvinist obsession with a nationalist will to power.

Like all dictators, Mussolini was explicit about his violent goals from the outset:

“The Fascist State expresses the will to exercise power and to command. Here the Roman tradition is embodied in a conception of strength. Imperial power, as understood by the Fascist doctrine, is not only territorial, or military, or commercial; it is also spiritual and ethical.”

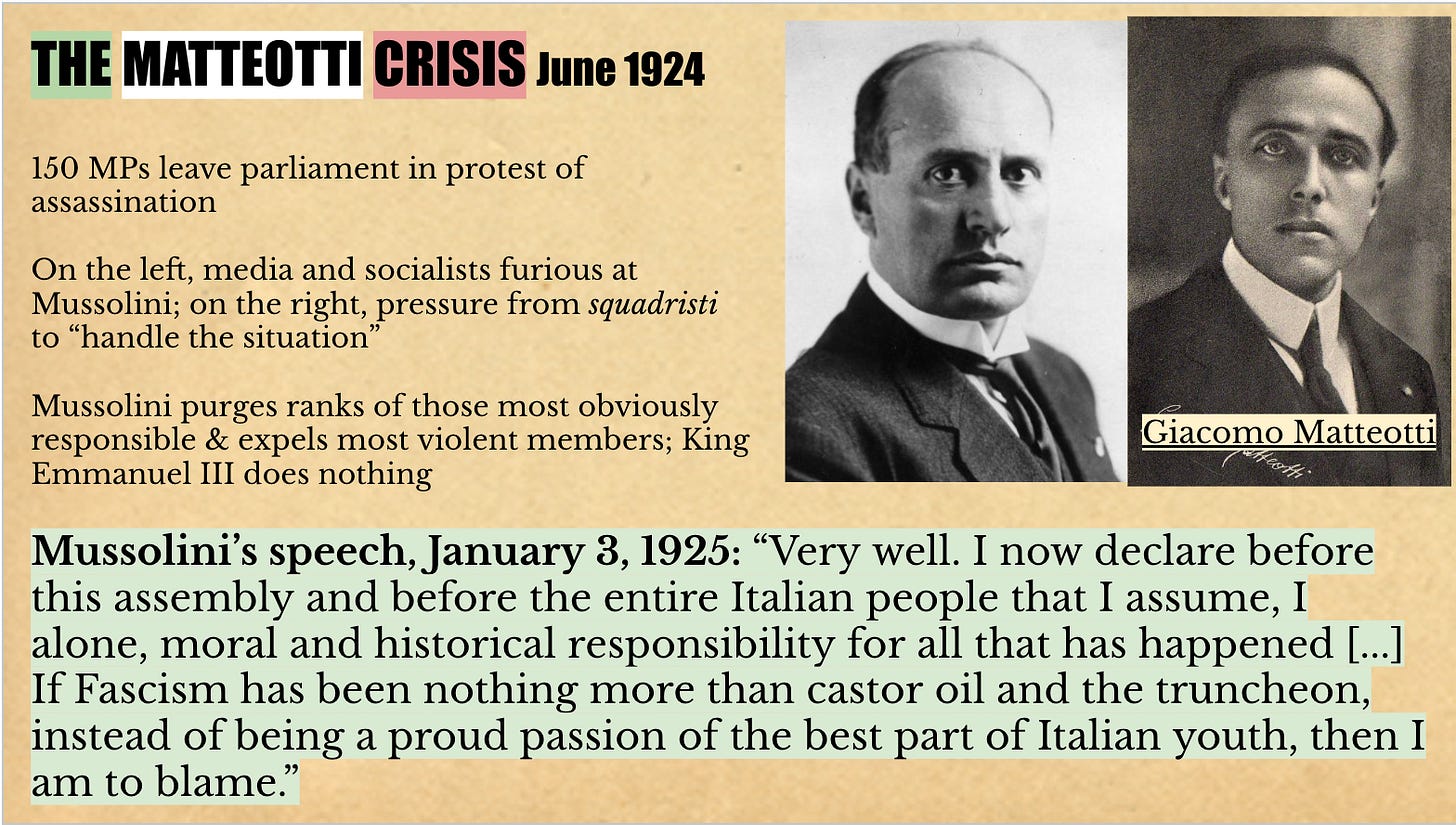

Despite the self-destructive dangers posed by a bellicose, hypocritical megalomaniac who’d started his political career as a dedicated communist, after Italy’s 1924 parliamentary elections, which Mussolini “won” with 65% of the vote (despite widespread reports of voter suppression, intimidation, and fraud), few elites were willing to challenge Mussolini’s gangsterism.

When Mussolini’s greatest political rival cried foul, the socialist Giacomo Matteotti, Matteotti was promptly kidnapped and assassinated. Instead of backing down from parliamentary and public outcry, Mussolini clenched his fists and further puffed out his chest, taking full responsibility for the violence on January 3, 1925:

“Very well. I now declare before this assembly and before the entire Italian people that I assume, I alone, moral and historical responsibility for all that has happened [...] If Fascism has been nothing more than castor oil and the truncheon, instead of being a proud passion of the best part of Italian youth, then I am to blame.”

The con worked. Nobody dared challenge his arrogance, and lo and behold, there wouldn’t be a free election in Italy for another twenty-one years (1946)

The Inferiority Complex Will to Power

“It is the feeling of inferiority, inadequacy, and insecurity that determines the goal of an individual’s existence. […] All our institutions, traditional attitudes, laws, morals, and customs give evidence that they are determined and maintained by privileged males for the glory of male domination.”

Alfred Adler, Understanding Human Nature, 1927

Alfred Adler believed humans are inherently weak, which is why we suffer from an inferiority complex. As we learned in Part II concerning Freud’s tragedies and their undeniable effect on his cultural theory, there’s no such thing as a social theorist whose personal life isn’t at the core of their philosophy, and Alfred Adler was no exception.

When Alfred was just three years old, he saw his brother die next to him in his bed. Soon after, Alfred developed rickets and pneumonia. He was also run over twice by vehicles before he reached puberty. If that weren’t enough to arouse extreme feelings of inferiority weakness, Alfred also envied his older healthier brother, Sigmund (let’s call it a strange coincidence that Alfred’s brother shared the same name as Sigmund Freud, whose work overshadowed much of Adler’s throughout his life).

Small wonder that the inferiority complex formed the basis of Alfred Adler’s view of the human condition. To overcome such feelings of weakness (and to harness the resulting will to power), Adler believed in what he deemed the social feeling, which requires a suppression of the ego in favor of cooperating with a community:

"To be good means to be good towards others, and to be bad means to be bad towards others […] Human beings strive for the happiness of others; this is the true pleasure of the socially interested person. The [Freudian] 'pleasure principle' is the striving of a person who is only interested in himself and not in others."

Alfred Adler, “The Meaning of Life,” The Lancet, 217 (1931), 226. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673600878290]

People often forget, however, that community isn’t by definition a good thing.

In fact, when a community’s identity is defined less by what it is than by what it is not (see: various ideological social movements in 2024), the result is a moralistic problematic definition of an in-group and an outgroup.

This principle is evident in Mussolini’s The Doctrine of Fascism (1932), which limits the virtue of the “social feeling” to a mythological idea of what it meant to be Italian:

[…] not a race, nor a geographically defined region, but a people, historically perpetuating itself; a multitude unified by an idea and imbued with the will to live, the will to power, self-consciousness, personality.”

Fascism only accepted the individual insofar as the individual embodied the virtues of the State; in other words, to achieve social unity and individual freedom, the Italian people had to submit to the State’s militant will to power. And while liberal democratic societies of the era defined “liberty” as equal rights for all, the Fascists argued that this went against the very principles of self-serving social hierarchy Social Darwinism, creating a zero-sum game that pitted ethnonationalism against all who sought to deny its claims to an entirely mythological history identity.

Like today’s billionaire capitalist corporate solipsists and the many hundreds of millions of wannabes, there were only two options in life: winning or losing. Fascism conceived “of life as a struggle in which it behooves a man to win for himself a really worthy place, first of all by fitting himself (physically, morally, intellectually) to become the implement required for winning it.” And so, to “win” this “worthy place,” Mussolini promoted violence against communists, foreigners, and anyone else deemed dangerous by championing violence and paramilitary groups (squadristi) that embodied the Fascist will to power.

Squadrismo & the Will to Power

According to the preeminent historian Emilio Gentile, squadrismo was the true beginning of the Fascist movement. Much like the post-WWI Freikorps units in Weimar Germany, squadrismo provided a cathartic outlet for disgruntled soldiers who’d returned to a post-war Italy they no longer recognized. Mussolini used these paramilitary units to quell socialist uprisings, crush factory strikes, and intimidate voters while promoting a conservative totalitarian value system of order, leadership, and discipline.

With its origins in rural politics, squadrismo also provided social mobility for working men (Fascism believed women should stay home) who derived spiritual purpose in rising through the ranks (see: boys clubs). According to Emilio Gentile, "of some thousand Fascist leaders who ran local organizations, 80 percent came from lower-middle-class backgrounds”—and since the State brazenly told the squadristi to sublimate their inferiority complexes via chauvinism, bigotry, xenophobia, and violence, members were united under a shared culture of violence via “action squads” led by local commandants who were obeyed with strict discipline and loyalty.

With its strong-armed solution to the inferiority complex, squadrismo placed the mirage of individual power in the hands of emasculated disillusioned foot soldiers who would one day be asked to die for the State. Importantly, however—and this is where we shall leave it for next time—the squadristi felt spiritually responsible to Mussolini Il Duce and all he represented, which meant that Mussolini’s political opponents were now existential enemies. And now that the supposed “fight for Italy” had become a matter of life and death, the stage was set for State-sponsored violence. Anyone who disagreed with Fascism thus disagreed with Italy’s past, present, and future. In this way, Fascism ceased to be a political party but rather a spiritual movement for which its acolytes were required to fight die (most notably during the 1935 Invasion of Ethiopia (where tens of thousands of Ethiopian men, women, and children were massacred) and during the civilian terror bombing campaigns in Spain between 1936-1939.

Within this culture of fear, violence, and aggressive will to power, the well-being of the individual ceased to mean anything outside of the well-being of the State. But to understand how Mussolini convinced hundreds of thousands of Italians to die in the name of an elusive myth, we must move further still, beyond the pleasure principle and the will to power, to consider Viktor Frankl’s theory of the will to meaning, which is the conclusion subject of Part IV of this essay, because it never ceases to amaze me how even in 2024, people are still surprised by humanity’s ability to be cruel self-destruct.

In conclusion, I’ll leave you with a Nietzschean phrase to ponder, which is at the core of what I believe about the human condition:

“He who has a Why can bear [or commit] almost any How.” Friedrich Nietzsche

The Origins of Fascism (Part IV)

Autocrats depoliticize their programs by creating an ethos, thus rendering their bigotry existential and inseparable from religious sentiments and moralistic concerns.

PS

I recently wrote a novel about love, fascism, and the human condition. It’s called The Requisitions, and its set during the Nazi Occupation of Poland. Some people on Goodreads say it’s worth reading. As of this post, 48 / 300 signed & limited 1st edition copies remain.

“I cannot think of any need in childhood as strong as the need for a father’s protection […] The origin of the religious attitude can be traced in clear outlines as far as the feeling of infantile helplessness.” Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents

Excellent series. It is easy to forget that fascism generally and Nazism specifically owed so much to the Italian experience in the 1920s. I appreciate the combination of history and its philosophical underpinnings. Thank you.

For those Free Spirits in training Nietzsche reminds us of the following in BGE 41 aka "cleavage"

One must subject oneself to one's own tests that one is destined for independence and command, and do so at the right time. One must not avoid one's tests, although they constitute perhaps the most dangerous game one can play, and are in the end tests made only before ourselves and before no other judge. Not to cleave to any person, be it even the dearest—every person is a prison and also a recess. Not to cleave to a fatherland, be it even the most suffering and necessitous—it is even less difficult to detach one's heart from a victorious fatherland. Not to cleave to a sympathy, be it even for higher men, into whose peculiar torture and helplessness chance has given us an insight. Not to cleave to a science, though it tempt one with the most valuable discoveries, apparently specially reserved for us. Not to cleave to one's own liberation, to the voluptuous distance and remoteness of the bird, which always flies further aloft in order always to see more under it—the danger of the flier. Not to cleave to our own virtues, nor become as a whole a victim to any of our specialties, to our "hospitality" for instance, which is the danger of dangers for highly developed and wealthy souls, who deal prodigally, almost indifferently with themselves, and push the virtue of liberality so far that it becomes a vice. One must know how TO CONSERVE ONESELF—the best test of independence.