The above video is a long-form conversation about literary fiction between me, the novelist , and the literary connoisseur . Big thanks to all who attended and my paying subscribers, who continue to inspire me to keep focusing on this space.

Paying subscribers: on the first weekend of each month, I will now be hosting a virtual lecture & discussion about literary Paris. The first lecture will be on Saturday, December 7 @ 5 pm CET / 11 am EST about Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald & the all-American price of pursuing wealth & fame as ends in themselves. I’ll send you a registration link at the beginning of the week & will also include it in next week’s post.

1

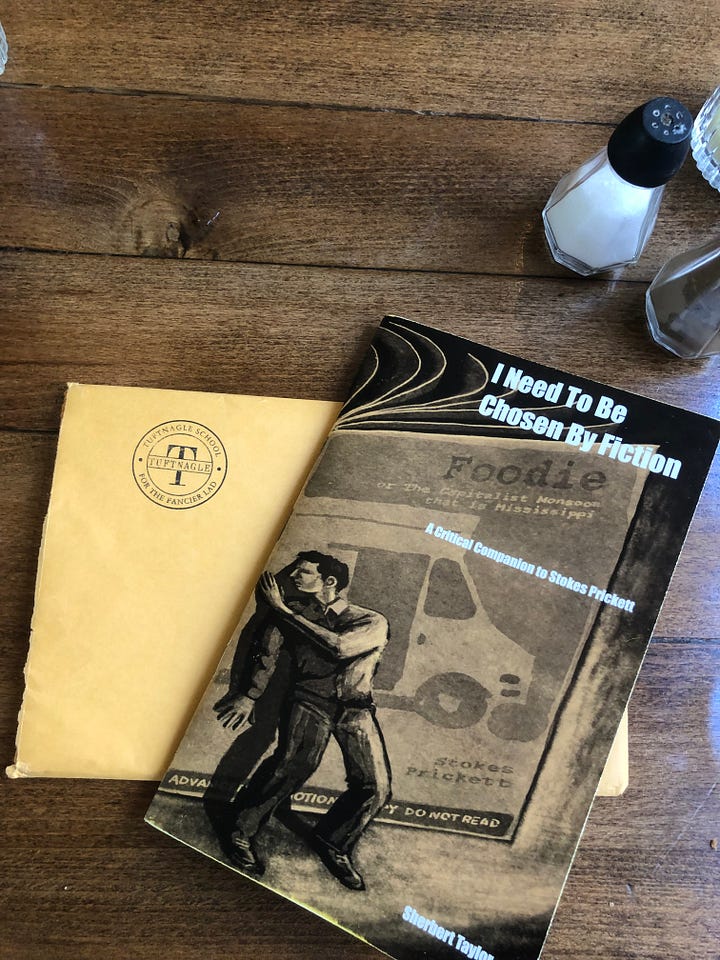

A few years ago, I wrote an essay titled “In Search of Artistic Integrity” about a pseudonymous author named “Stokes Prickett.” In 2020, the mystery author secretly began sending independently printed installments of a novella called Foodie or The Capitalist Monsoon that is Mississippi to unsuspecting readers across the USA.

The recipients included artists, writers, editors, DJs—anybody “Prickett” deemed worthy of receiving the mysterious missives—and to the delectable surprise of the lucky few who received a copy of Foodie, the writing storytelling was abnormally good—so good, in fact, that the writer

Foodie came and went without much fanfare, however, partly because “Prickett’s” identity was never discovered, but mostly because whoever “Prickett” was, they explicitly did not want to reveal their actual identity.

2

Foodie might be a perfect example of literary fiction.

From the few excerpts I could read, the writing was provocative subversive, an essential aspect of a genre often defined by subverting market-driven plots, character tropes, linear narrative structures and linguistic constructs.

But Foodie is also an example of literary fiction because of its disruptive publication model.

When it comes to publishing literary fiction, many folks’ opinions remain trapped in the brown amber of a myopic academy economy that favors traditionally vetted publishers over the rich history of independently published literary fiction.

Here are a few examples because I promised myself I wouldn’t turn this into a long-form essay:

In 1917 in London, Mr. and Mrs. Woolf

founded the Hogarth Press,bought a printing press, set it up in their kitchen, learned how to use it, and proceeded to publish the likes of Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, E.M. Forster, Theodore Dostoevsky, Jacques Lacan, and dozens of other literary greats. Importantly, they didn’t ask anybody for permission.Five years later, a legendary Irishman with an eyepatch who was struggling to find a publisher for his magnum opus inspired a young American bookseller in Paris named Sylvia Beach to publish James Joyce’s Ulysses independently.

Five years later, in 1927, Mr. And Mrs. Crosby

founded Black Sun Pressbegan independently publishing their obscure poetry. Within a few years, they were also publishing Oscar Wilde, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Lewis Carroll, Ezra Pound … the list goes on, and to this day, firs-edition Black Sun Press books remain some of the most highly sought after in the world.

Other Anglophone examples include Obelisk Press, which published Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer in 1932; Olympia Press, which published Beckett, Nabokov, and Burroughs in the 1950s; City Lights Books, which published the Beat Generation; Grove Press in New York City … the list goes on.

But while many of these authors’ writing style is indeed considered literary fiction because it subverts various structural, linguistic, and narrative constructs, what makes these examples of literary fiction so important, Foodie included, is that

authentic literary fiction subverts the publishing industry, too—and perhaps even suggests it has a responsibility.

3

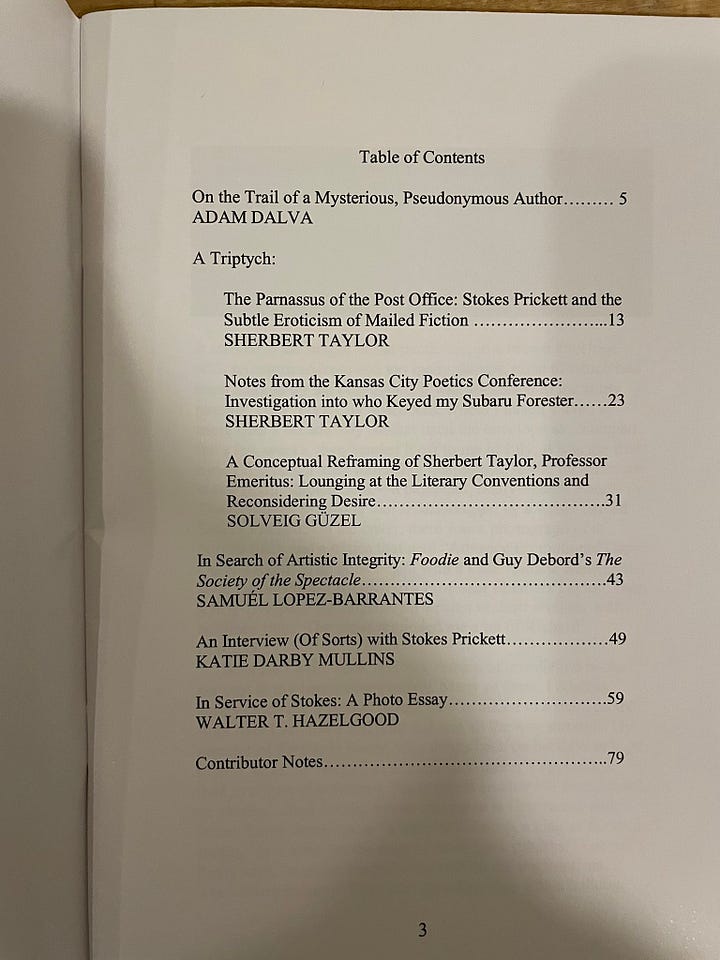

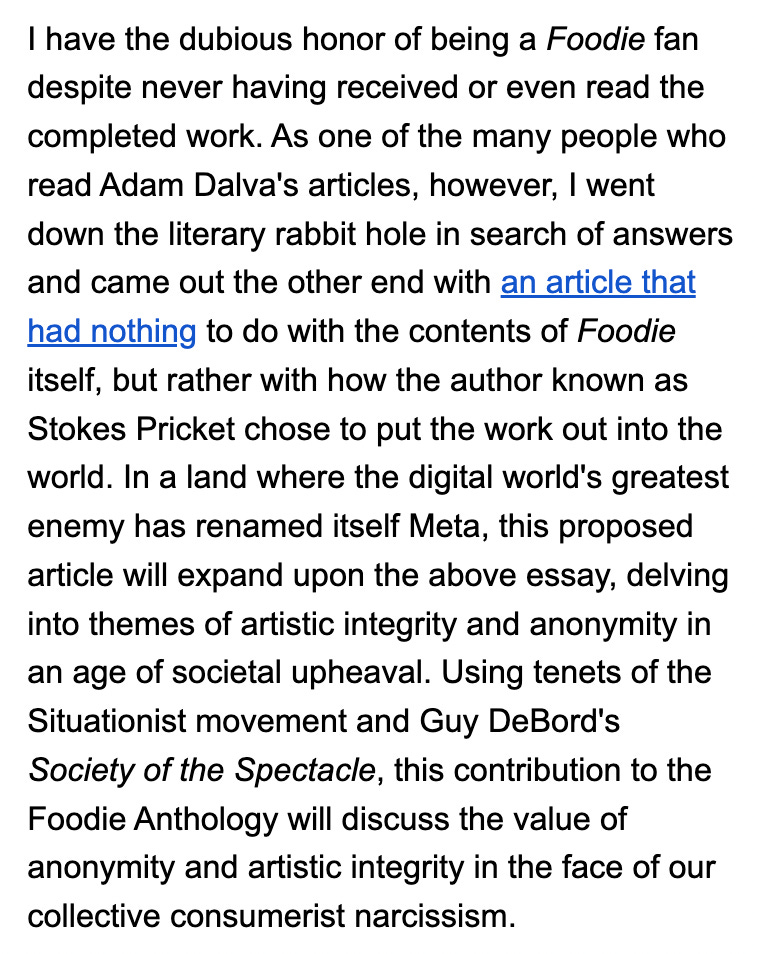

In December 2021, about a year after publishing my essay on “Prickett’s” subversion1, I submitted the piece to an anthology being compiled by someone related to (or perhaps body-snatching?) “Stokes Prickett.”

This is what I wrote:

A few days later, my proposal was accepted. Still, after a year of no news, I’d forgotten about the submission entirely until my singer/songwriter friend

sent me a text message in March 2023 that made me blush:Ryan: “Did you know this exists? You’re part of the story now my friend.”

4

It was a small but galvanizing literary win. At that time in my life, my thirty-something self was facing the prospect of hefty student loans for an underwhelming MFA, I was disillusioned with teaching creative writing at the Sorbonne, and I’d just completed a final draft of The Requisitions, the culmination of a decade of writing and academic research a literary/historical metafiction set in both the present-day and Nazi-occupied Poland.

While I’d been toying with the idea of querying dozens of agents and waiting multiple years in hopes of securing a publishing deal for little to no control over the design process and less than (at best) 15% of profits, deep down, I knew I couldn’t in good conscience go down the traditional publishing route with “Stokes Prickett’s” subversive publishing style on my mind.2 Instead, I began envisioning a different way of bringing The Requisitions into the world, and the rest, as they say, is historiographic metafiction The Requisitions.3

AND NOW A SPECIAL HOLIDAY OFFER

5

I’d foregone my Capitalist Monsoon Dreams of becoming a “Big Five Four” published author,

but in return I gained something much more valuable, perhaps: a deep sense of professional agency and personal accomplishment that has in turn connected me with newfound digital friends like

and and generous early reviewers of The Requisitions like and , all of whom are subverting the literary fiction world in their own ways.Epilogue

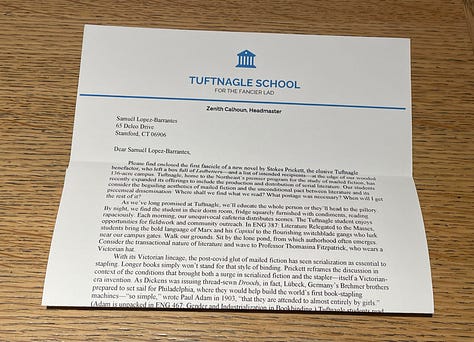

A few weeks ago, I received another missive.

Dear Samuél, the letter began, please find enclosed the first fascicle of a new novel by Stokes Prickett …

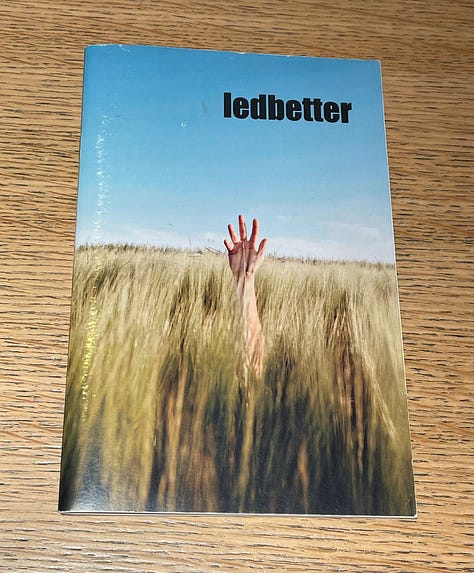

The envelope included a stapled pamphlet of the first 48 pages of Ledbetter, a fast-paced, beautifully written picaresque novel about a heartbroken artist-in-recovery who moves to Delaware to repair a wooden boardwalk:

“I belonged to no bureaus. I trafficked in universals, my nightstand piled with treatises. I inched toward understanding. My feverish years behind me, no lingo to learn, I dedicated myself to the boardwalk.”

The book’s immediacy and playfulness reminds me of Kurt Vonnegut or Tom Robbins—“being alone is like the moon, hanging world-weary and sexual, a swell of socialism a-brewing”—and its philosophical bent reveals an existentialist living in the USA who’s constantly flirting with absurdism:

The most terrible part of art dreams must be realizing that to keep on despite failure can come to seem just as sad as quitting. One’s purpose, as it were, either abandoned or unachieved, and yet people carry on tap-dancing or formulating their misunderstood free verse, helpless to distinguish between the brink of success and the last gasp.”

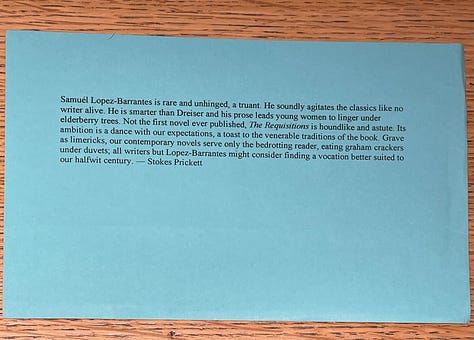

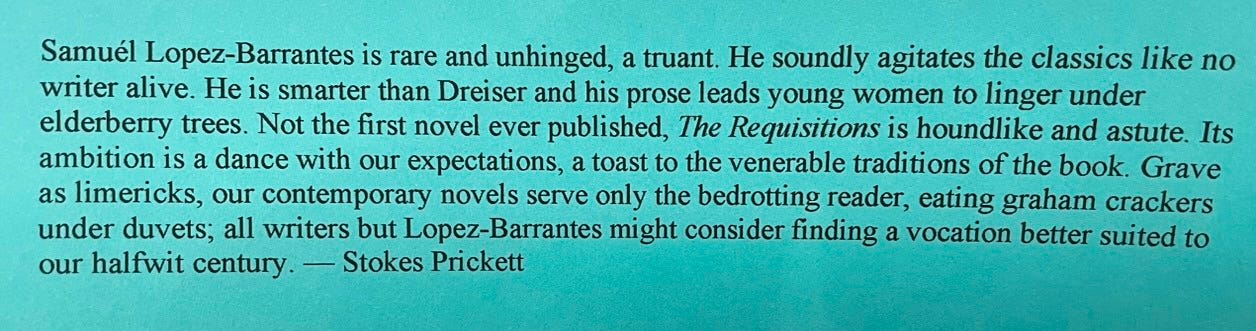

The last piece of paper in the envelope was the most unexpected:

a rectangular piece of blue paper that includes a thoughtful, hilarious blurb about The Requisitions, written by none other than “Stokes Prickett”:

Just one slight amendment, “Stokes,” if I dare be so bold: as I suspect is the case with you, writing is less a vocation than a lifelong beloved affliction, so here’s to the literary fiction renegades who seek a different kind of fortune fulfilment—

not just in how we write it but in how we publish, too.

In Search of Artistic Integrity

Three years after various book critics, writers, musicians, and artists began receiving unsolicited “advance promotional copies” of Foodie, the book has returned to obscurity, and this may be exactly what the pseudonymous author “Stokes Prickett” intended.

In December 2022, I bought back the rights to my debut novel. As a semi-professional musician in an indie-rock band, I left that industry after experiencing the pitfalls of signing with a craven music label that all-but buried our most authentic musical selves (happy ending: we started playing acoustic sets again for the fun of it)

In December 2023,

and I created Kingdom Anywhere, an anglophone Parisian micro-press, and sold out of a limited-edition of 300 copies of The Requisitions (“Stokes” received copy #203 of 300) before we published a global edition.Kingdom Anywhere

Augusta and I called our imprint Kingdom Anywhere because we believe in a world in which artists can thrive by placing principles front and center—and what is a kingdom, after all, if not a worldly community?

Share this post